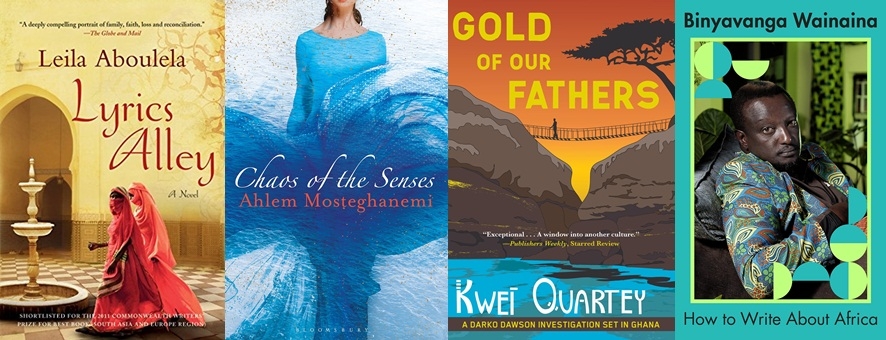

VIKAS DATTA It was called the "Dark Continent", not only due to lack of (European) knowledge of its expansive hinterland, but also for political reasons. Terming Africa backward and unenlightened gave colonial powers license to seize huge swathes of territory for "development" and "progress" of the natives. Unfortunately, the common stereotypes still persist in much of public - and literary - consciousness elsewhere. There are 54 independent countries on the continent, but for most of the outside world, all its ('black') people, outside the handful of Arab-speaking countries in the north, are thought as one. Take crime reports, usually relating to drug seizures, in Indian newspapers - "Narcotics worth Rs 1.5 crore seized, two Africans arrested", "Three African nationals arrested in Dwarka; 1 kg heroin seized" or "Noida: Three African men arrested for cheating people by posing as customs officials". Have you seen this used for people from other continents? This amorphous lumping is not far apart of the stereotypical cultural descriptions of Africa, as usually as the land of poor, illiterate, sick blacks living in hut villages/untamed wilderness and at the mercy of repressive/grossly corrupt governments led by unbalanced, egoistical leaders as political instability rages, since the transition from colonial rule. Big business and superpower rivalry also figures somewhere when it comes to national resources and aid. It is the "Wakanda" type (as from 2018 film "Black Panther" - but not that technologically advanced), a small country nestled somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa with thick jungles or parched savannahs, the residents a mix of white and blacks (the latter speaking pidgin English mostly). Evelyn Waugh's Azania from "Black Mischief" (1932) and Ishmaelia from media satire "Scoop" (1938) are early examples. Then there is Zangaro in Frederick Forsyth's "The Dogs of War" (1974), Zanj, Kush, and Sahel in John Updike's "The Coup" (1978), and Zamzarin in William Boyd's James Bond novel "Solo" (2013). Earlier, and even worse, there was "Darkest Africa" approach - even if the the setting was sandy wastelands, the grassy plains, the ruins of mysterious, unknown civilisations, or usually, the dense, treacherous jungle. You can see this in Lee Falk's Phantom, Edgar Rice Burrough's "Tarzan", H. Rider Haggard's "She" and "King Solomon's Mines", Michael Crichton's "Congo", Jules Verne's first-published work, "Five Weeks in a Balloon", Edgar Wallace's "Sanders of the River" series - posthumously continued bu Francis Gerard, Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" - using African wilderness to contrast a character's descent to savagery, and almost everything written by Wilbur Smith. All, or most of these works, were also marked by the presence of the "Mighty White Hunter/Explorer" who made discoveries/restored peace/kept order, and so on, of course, helped, by the wise native advisor/warrior/tracker or other noble savages. As Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina remarked: "Always use the word 'Africa' or 'Darkness' or 'Safari' in your title. Subtitles may include the words 'Zanzibar', 'Masai', 'Zulu', 'Zambezi', 'Congo', 'Nile', 'Big', 'Sky', 'Shadow', 'Drum', 'Sun' or 'Bygone'. Also useful are words such as 'Guerrillas', 'Timeless', 'Primordial' and 'Tribal'." "Taboo subjects: ordinary domestic scenes, love between Africans (unless a death is involved), references to African writers or intellectuals, mention of school-going children who are not suffering from yaws or Ebola fever or female genital mutilation," he added in "How to Write About Africa". However, there are a host of writers - American, British, Australian - who have dealt with Africa, be the colonial period or the present, with better understanding. They include William Boyd with "A Good Man in Africa" (1981), "An Ice-Cream War" (1982), "Brazzaville Beach" (1990), Robert Wilson with his West African noir crime series comprising "Instruments of Darkness" (1995), "The Big Killing" (1996), "Blood Is Dirt" (1997), and "A Darkening Stain" (1998), while Nicholas Drayson's "A Guide To The Birds Of East Africa" (2009) and "A Guide To The Beasts Of East Africa" are an engaging look at the Indian diaspora in Kenya. Then, there is Alexander McCall Smith's "The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency" series. But, let's look at some five-six works of writers from across the continent, especially from countries usually underrepresented on the global literary map. This will rule out South Africa - which has two Nobel Literature laureates already in Nadime Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee, Egypt with Nobel winner Naguib Mahfouz and a vibrant literary scene, and Nigeria, where Wole Soyinka became the first Black African to receive the Nobel (it took 35 years before Abdulrazak Gurnah became the second). Let's begin with Sudan - the continuum between Arab north Africa and the rest of the continent where the people are mostly culturally Arab but look "African". (Confusingly, there is also a geographical sub-Saharan area of 'Sudan', which doesn't include the country, as it forms a belt between the Sahara Desert and coastal West Africa). Leila Aboulela is one of the foremost Sudanese authors, even though living in Scotland and writing in English. While her debut novel "The Translator" (1999) is the story of a young Muslim Sudanese widow living in Scotland and her developing relationship with Scottish Middle Eastern scholar, her "Lyrics Alley" (2011) is an absorbing read. Loosely adapted from her own family, it is an evocative account of a prominent business family in Khartoum as the country moves towards independence from the UK (and Egypt) and how fate trumps its patriarch's succession plans, and the conflict between his first traditional-living wife and second, modern one wreaks havoc for the latter's daughter, but, above all, of the resiliency of the spirit. Algeria, the largest country of the continent, has also a vibrant literary scene, right from the colonial period - Albert Camus and Frantz "Black Skin, White Masks" Fanon being some prominent examples. It does fall in the Arab cultural space, though its version of the language is quite different for other Arab speakers, and there is also the Berber influence. Ahlem Mosteghanemi is deemed the top-selling woman Arabic author and her trilogy - "Zakirat el Jassad" (1993), "Fawda el Hawas", and "Aber Sareer" show why. They are available in English as "The Bridges of Constantine" (2013), "Chaos of the Senses" (2015), and "The Dust of Promises" (2016), a lyrical and heart-tugging about loss and remembrance, exile and belonging, and love and longing. The first covers over four decades of Algerian history as it interweaves the characters' life trajectories and memories from 1945 to 1988 when Khaled, the protagonist-narrator who fought in the liberation war, is writing a memoir of his in the form of the novel we read. Living in exile, his life undergoes tumult when Hayat, the daughter of his old revolutionary commander and now an enticing young woman novelist, unexpectedly reenters his life. The second takes up the story of Hayat who is trapped in a loveless marriage to a senior security official as the Algerian civil war rages and finds solace in a forbidden and singular love affair. while the third brings destiny of Hayat, Khaled, and the narrator of the second book to a heady conclusion in Paris. Travelling southeast to Zimbabwe of Robert Mugabe, we have Tendai Huchu's "The Hairdresser Of Harare" (2015). It seems a frothy comedy of manners till its somewhat disturbing denouement but is actually deftly served socio-political commentary with pity observations on classism, racism, and homophobia. It tells of a woman stylist in a Harare hair salon, who seems upstaged by a new male employee. They get close eventually but then she discovers something untoward - some readers might see where there is heading to. Kwei Quartey, the son of a Ghanian father and an African-American mother, started writing along his medical career in the US. His Inspector Darko Dawson series - "Wife of the Gods" (2009), "Children of the Street" (2011), "Death at the Voyager Hotel" (2014), "Murder at Cape Three Points" (2014), "Gold of Our Fathers" (2016) and "Death by His Grace" (2017) are innovative, intricate, and atmospheric crime stories that well capture the flavour of Ghana. His latest - "The Missing American" (2020), and "Sleep Well, My Lady" (2021) - bring in woman private investigator Emma Djan, with a nod to Raymond Chandler's style. Finally, we come back to Wainaina, who tragically succumbed to a stroke in 2019, aged 48. If the excerpt from his 2005 satirical essay whetted your appetite, wait for "How to Write About Africa", a collection of his trenchant writings on politics, cultural heritage and redefining sexuality and more besides, due to be published in September this year. (Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

'This time for Africa': Fair writing of and from the continent

- by Rinku

- April 03, 2022 2 minutes

This time for Africa