VISHNU MAKHIJANI New Delhi, July 4 (IANS) The soul of Peter Brook's work as a director, actor and writer was in his productions noted for what he called "colour-rich", as opposed to "colour-blind", casting. In his view, when the audience sits bored, listening to a recital of words with no emotion, the actor has failed. Brook once said: "People have entrusted themselves to you for two hours or more and you have to give them a respect that derives from confidence in what you are doing. At the end of an evening, you may have encouraged what is crude, violent or destructive in them. Or you can help them. By that I mean that an audience can be touched, entranced or -- best of all -- moved to a silence that vibrates round the theatre." And this, literally, brought the roof down on the opening night of William Shakespeare's 'Timon of Athens' at the once-dilapidated Bouffes du Nord theatre in Paris that he helped restore. The applause shook the building. "There were various problems on the opening night. It was a big success but the applause brought down some of the ceiling. People had bits of plaster on their heads," Brook said in an interview to Chris Wiegand, Stage Editor of 'The Guardian' newspaper in 2016. How did the turnaround happen? "I wanted that Elizabethan feeling where if you come to the theatre, you mix with all people -- not just the rich. We had people sitting on the ground from the start. Actors were in close contact with the audience, reacting immediately with them. The acting space was much further forward than it had been when it was a proscenium theatre. So we had this proximity with the audience but there was also this great, vast space reaching to the back wall -- that was important to depict Timon after his exile." Brook explained. "We put in steps coming up from the pit, so actors could make spectacular entrances. We used cubes and boxes, very rough things. The designer wanted to find how we could make clothes that were free of associations, yet true to the actors. The Bouffes is now surrounded by Indian shops and restaurants but at that time there was nothing Indian in the area. "So our designer went to the African market nearby and got all sorts of fine clothes and made simple new shapes with them. These were definitely not modern dresses, but simple clothes, to which you have no immediate connections -- such as to Elizabethan or Victorian times -- in your mind. We continue to use that approach today. "The theatre's fine acoustics enabled you to feel as if you were playing in a courtyard in the open air, yet the space also had an intimacy that made it possible for the actors to play as if they were in a film. That was the double nature of the Bouffes, and what Timon -- and any Shakespeare play -- demands. "You mustn't make it cosy and intimate at the expense of its heroic, epic qualities and you mustn't make it epic and heroic at the expense of the fact that, moment by moment, it's all about real people and real feelings," Brook said. In a 2017 interview with British art critic Michael Billingron, Brook spoke about how important it is to "swim against the tide and achieve whatever we can in our chosen field. Fate dictated that mine was that of theatre and, within that, I have a responsibility to be as positive and creative as I can. To give way to despair is the ultimate cop-out." Not surprisingly, after his productions at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and the Bouffes du Nord, his base for more than 30 years was in African villages where his actors improvised performances, and on stages both grand and in modes that his globetrotting ensemble visited refined the way theatre is looked at. Brook's landmark achievements include a nine-hour version of the 'Mahabharata', putting Shakespeare on trapezes, and directing the likes of Sir Laurence Olivier, Sir John Gielgud and Paul Scofield at the RSC. 'The Mahabharata', in fact, was staged in a French quarry in 1985 and 'The New York Times', noting its "overwhelming critical acclaim", said it "did nothing less than attempt to transform the Hindu myth into universalised art, accessible to any culture". Many post-colonial scholars, however, have challenged this claim to universalism, accusing the play of Orientalism. Author Gautam Dasgupta wrote: "Brook's Mahabharata falls short of essential Indianness of the epic by staging predominantly its major incidents and failing to adequately emphasise its coterminous philosophical precepts." Brook returned to the epic in 2016 with 'Battlefield', staged with his long-time collaborator Marie-Helene Estienne. Brook also directed musicals, the anti-Vietnam war protest play 'US', and co-created with British author Ted Hughes 'Orghast', an experimental play based on the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus, a Titan and god of fire. "I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space, whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged," Brook wrote in 'The Empty Space' (1968), which many directors and actors consider their Bible. For instance, Brook's 1970 version of 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' for the RSC, influenced by both a Jerome Robbins ballet and the Peking Circus, was performed in a white cube of a set and boasted trapezes, stilts and a forest of steel wire. Often referred to as "our greatest living theatre director", Brook won multiple Tony and Emmy Awards, a Laurence Olivier Award, the Japanese Praemium Imperiale and the Prix Italia. The Government of India honoured him with the Padma Shri in 2021 "for his valuable contributions towards art". Born in London on March 21, 1925, at age seven he acted out a four-hour version of 'Hamlet' on his own for his parents. After attending Magdalen College, Oxford, he was soon at the Royal Opera House, directing Richard Strauss's opera 'Salome' with designs by Salvador Dal'. He directed Laurence Olivier as Titus Andronicus in Stratford for the RSC in 1955 and when Peter Hall became its artistic director in 1958, he asked Brook to assist him there. Brook's RSC productions included a 1962 staging of 'King Lear', a play he considered "the supreme achievement of the world's theatre" that starred Paul Scofield. Several of his shows received Broadway transfers, including the avant garde 'Marat/Sade', which won the Tony award for best play in 1964. The concept was that the Marquis de Sade was putting on a drama about the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat, acted out by the inmates of a mental asylum. In 1970, Brook moved to Paris, where he set up his International Centre for Theatre Research. The company visited Africa, where his actors gave performances that "didn't use anything that corresponded to the theatre of the time -- we wanted to play to audiences who were not conditioned by anything. We wouldn't, even experimentally, do a play with a text or a theme or a name." 'The Man Who', which premiered in Paris in 1993, was inspired by neurologist Oliver Sacks's book 'The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat', which revisited the disorders of Sacks's patients. Brook's own neurological research led to 'The Valley of Astonishment', about synaesthesia, co-created with Estienne, and performed at the Young Vic in London with Kathryn Hunter among the cast. Brook married the actor Natasha Parry in 1951 and they had two children, Irina (now a director) and Simon (now a producer). Parry died in 2015. "We have lost a beacon.... He didn't just believe in the profound humanity and transformative power of theatre and Shakespeare, he put it into action. He was a true and rare practitioner and his legacy must live on in those of us who humbly follow in his eternal summer," Michelle Terry, artistic director of Shakespeare's Globe, said of Brook's passing.

The influential stage visionary who made 'Mahabharata' a global epic

- by Rinku

- July 04, 2022 2 minutes

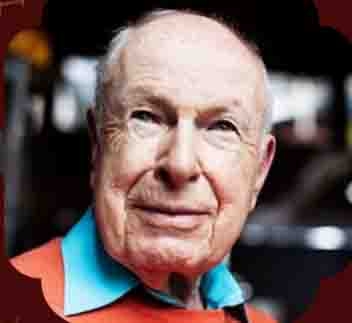

Peter Brook. (Credit : @mygovindia/twitter)