By Major General Ashok Kumar (Retd) There have been multiple air operations world over with varying outcomes from which some lessons can always be drawn. However, the paradrop at Tangail on December 11, 1971 by India was a key catalyst of the war to ensure Indian victory in East Pakistan, surrender of more than 93,000 Pak troops (unparallelled in the history of warfare) and the liberation of Bangladesh. The importance of Tangail can be gauged from the fact that an entire Pakistani Brigade was enveloped and cutoff from retreating, trapping them in the process. This enabled them to stop the reinforcement of Dacca (now Dhaka) and facilitated its early capture by General Sagat Singh's formations. A shock action like this recalls the early breakthrough by German paratroopers during the capture of Fort EbanEmael in May 1940, leading to the capitulation of Belgium. Even there a puny force of 78 German parachute-engineers commanded by a Lt Witzig captured an entire fort of 1,200 Belgian troops, with a loss of only six men. Shock action by paratroopers is part of a shock action strategy that creates a psychological effect in the adversary's mind and supplements the sometimes small strength of the attacking contingent with psychological warfare. Though the size of the paradrop in Tangail was limited to a battalion, i.e., 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, which landed at 16:30 hrs on that fateful day of December 11, it created an awe and shock effect for the Pakistani troops of 93 Brigade. When combined with BBC reports about a large body of Indian troops moving with lightning speed towards Dacca, it created such an impact on the Pakistani leadership that it opted to surrender immediately, rather than fight till the last, as famously advertised by General A.A.K. Niazi in Dawn newspaper. The strafing of the house of the Governor of East Pakistan by a flight of MiG 21s led by Wing Commander B.K. Bishnoi helped the cause. Another example of shock action from above is 2 Para linked up with another infantry battalion that achieved much more than what was aimed at. While a large number of air operations were conducted in 1971 both on the Western and Eastern front, the paradrop on December 11 stands out as a joint operation between the Indian Army, Indian Air Force and the brave Bangla patriots (Mukti Bahini personnel and local civilians came forward on their own and assisted in lifting the heavy baggage of soldiers, hastening the march to Dacca and bolstering their morale). India had just achieved its hard-earned Independence from the British in August 1947 when a war was thrust upon it in October 1947 with the arrival of tribal raiders and Pakistani regulars in Jammu and Kashmir. During the war of 1947-48, the Indian Air Force was involved in airlifting troops to Srinagar. This action was the prime reason for stalling the progress of Pakistan-sponsored militants and soldiers who were intent on snatching a legal part of India through the illegitimate use of force. They were later pushed back, which resulted in Pakistani control being limited to one-third of Kashmir due to a UN resolution which resulted in a ceasefire. It is, however, a matter of surprise and speculation why the Indian Air Force was not used offensively against Chinese troops during the 1962 war. This is despite the Air Force possessing nearly 22 combat squadrons and over 500 aircraft. The IAF limited its use only to helicopter and transport crew sorties to service forward pickets in the then North Eastern Frontier Agency (NEFA) and Ladakh. India restrained itself despite suffering reverses in the 1962 war. In the absence of declassified documents, analysts have made a few guesses as to why the IAF was underutilised in 1962. Inadequate reading of the war preparedness of the Chinese, under confidence in own abilities by the then Chief of Air Staff may have been a few reasons. It is believed that the use of air power in offensive mode in 1962 could probably have changed the outcome of the war and we could have been sitting in a more favourable situation vis-a-vis the LAC in Eastern Ladakh, even if the entire Aksai Chin was not in our reach due to adverse weather and geographic conditions. As we moved ahead in time, we used air power extensively in 1965 and 1971 wars with favourable outcomes. Its usage in 1971 took us to the league of war hardened nations and group of war winners. In fact, India is the only country in the world which affected the creation of a new nation-state, recognised globally in a matter of months. Over all these years, our air power developed, but due to its predominant focus on Pakistan, its capabilities in high altitude remained restricted, which came to the fore during the Kargil war. Despite the marginal use of airpower necessitated by geopolitical compulsions and India's desire not to cross the Line of Control, the IAF's response proved wanting. Conflict scenarios in the subcontinent and globally have since undergone a major paradigm shift. China looms over India as a potential adversary as well as an aggressor wherein it disregards all the previous agreements with India. China has continued with its geographic creep all along the Indian borders in Eastern Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. With the passage of land boundary law in October 2021 that's slated for adoption on January 1, 2022, it has already changed the territorial dispute into sovereignty dispute, while flexibility during mutual negotiations have also shrunk. In such a scenario, the IAF needs to be ready for multiple Tangail like contingencies and prepare for a future scenario where airpower needs to shape the scenarios. (Major General Ashok Kumar, VSM (Retd), is a Kargil war veteran and defence analyst. He is a visiting fellow at CLAWS and specialises in neighbouring countries with special focus on China. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at akumar157@gmail.com)

Shock action from above: What can we learn for future warfare?

- by Rinku

- December 21, 2021 2 minutes

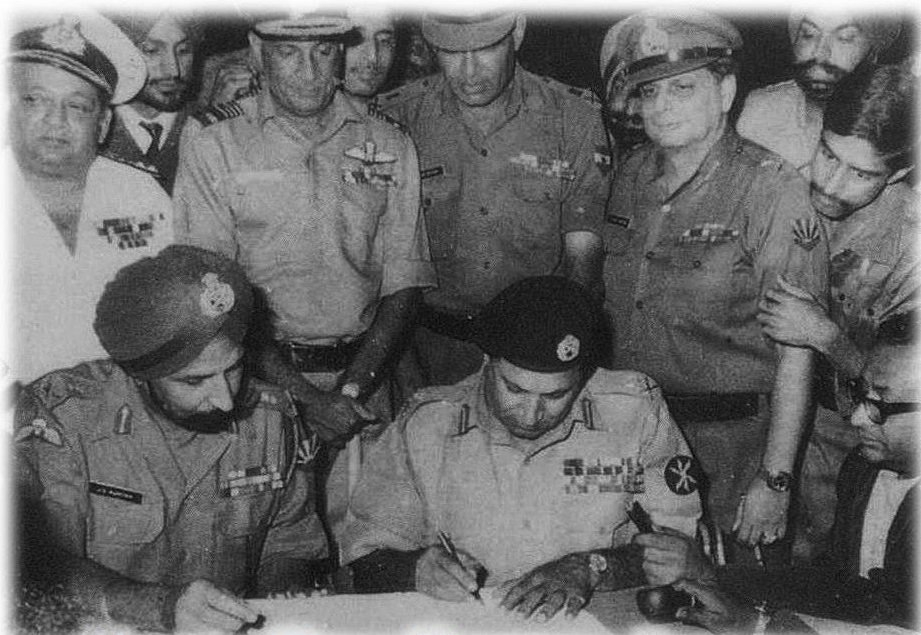

On the occasion of Vijay Diwas 2019, CISF remembers the indomitable spirit of the brave soldiers who fought in 1971 Indo-Pak War. (File Photo: IANS/CISF)