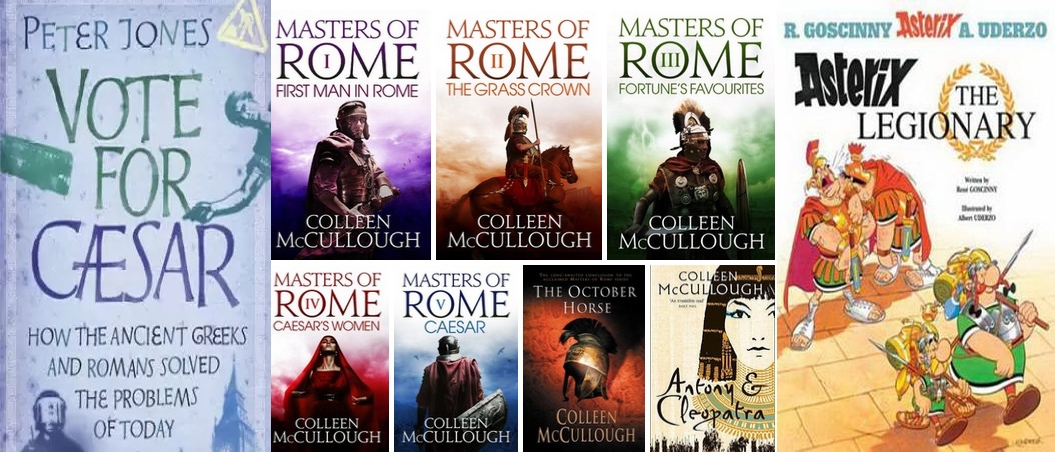

VIKAS DATTA How can we define the significance of an ancient civilisation? One obvious yardstick could be how proud its purported descendants are about it, but this is far from objective, and in the social media era, ill-informed too. A more valid criterion will be to see how its influence survives today, or say, how at home we would be if we are somehow sent back to one of these civilisations? On both these standards, ancient Rome, say in the late Republican period (1st century BCE), could well qualify. In Rome of this period, you would find yourself in a large sprawling city, where plush neighbourhoods with elegant villas are interspersed with more crowded areas full of multi-storey buildings, streets teem with people from all over the known world, there are markets and various services, common people eagerly follow and gossip over the foibles of the rich and famous, are swayed by sops and entertainment spectacles, stay keenly involved in governance which, however, is largely a preserve of professional politicians with issues over public works, food subsidies, corruption et al predominating. Unlike most other ancient civilisations across Europe, Asia, and Africa in the period, where nascent democracy - be it in Greece or India - was limited and soon snuffed out by monarchs -- Philip and Alexander in Greece, Ajatshatru in India, Republican Rome (4th-1st century BC) bucked the trend. In the last decade of the 5th century BC/BCE, its people overthrew a monarchy that was in place since its legendary foundation date of 753 BC to become an oligarchic republic - like most of the present-day democracies -- with a defined tenure for its leaders selected through open elections involving all citizens (save women -- but then voting rights for women would not come till the early 20th century). And their "mission" resonates with the Indian ethos too. As it became a major power, Rome had the credo "....imponere morem pacis, parcere subjectis et debellare superbos (Spread peace, spare the subdued, vanquish the arrogant)", a sentiment quite in line with Lord Krishna's assertion in the Bhagavad Gita: "Paritranaya sadhunam vinashaya cha dushkritam dharma-samsthapanarthaya ... (help the good, destroy the wicked and establish just order on earth)". Republican Rome, with all its advantages and problems, lasted for nearly five centuries till nearly a century of civil war and social tensions swung the clock back to an empire. But the Ancient Romans' influence survives till now - in language, governance (the Senate is still the most powerful legislative body in a number of countries), architecture and engineering (aqueducts, sewers, bridges, and a type of cement that still impresses experts now), law, and of course, culture -- as it predominated then and was spread around by them in the expansion of the rule around the Mediterranean littoral and further. As a character, in what was then the Roman province of Judea, in that splendid comic satire "Life of Brian" (1979) petulantly asks "All right, but apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, the fresh-water system, and public health, what have the Romans ever done for us?" While modern law, botany and zoology, and medicine could hardly do without Latin phrases and words, everyday English is also full of them. The names of our months are the biggest legacy, and then, words such as agenda, ambidextrous, authority, capital, calculator, century, citizen, cosmopolitan, consult, circus, dignity, forum, introspection, imperial, liberty, magistrate, money, obeisance, republic, sacrifice, salary, stipend, triangle, ultimatum, urban, wine, and many more, are all Latin constructs deriving from Roman concepts. Then, cultural depictions of the Roman times are always popular and frequent - movies like "Spartacus", "Ben-Hur", "Quo Vadis", "Cleopatra", plays like Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar" or "Coriolanus", the Asterix series, and historical fiction by Colleen McCullough, Robert Harris, Howard L. Fast, Steven Saylor, Conn Iggulden, Ben Kane and so on. If you should want to know more about Ancient Rome, there is no shortage of reading material - histories abound from Edward Gibbon's voluminous six-volume "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire". A more accessible and modern work is Cambridge classicist Mary Beard's "SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome" (2015), which not only tells us about Roman history from the formation of the city in the 8th century BCE but also how we know about them os basis of architectural and textual knowledge and how the Romans saw themselves and their history so far. Then, fellow Cambridge scholar Peter Jones offers "Veni, Vidi, Vici: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about the Romans But Were Afraid to Ask" (2013) and "Quid Pro Quo: What the Romans Really Gave the English Language" (2016), while "Vote for Caesar: how the Ancient Greeks and Romans solved the problems of today" (2008) is self-explanatory and an engaging and thoughtful read too. However, it is Australian author McCullough, best known for "Thorn Birds", who brings the late republican epoch into vivid life with her 'Master of Rome' series. Initially, it comprised six books, spanning from 110 BCE to 42 BCE, but on popular demand, including from the then Australian Prime Minister, she wrote a seventh, taking the narrative down to 27 BCE, when the Roman Republic segued into the Roman Empire. A template for the historical novel, the series displays meticulous research, the plot follows the line of actual happenings, and though McCullough does use her imagination to fill in the gaps, she is as far as possible on the side of probability - and goes on to discuss her reasoning in an afterword. The result is a magnificent, multi-layered account bringing to life the 1st-century Mediterranean world, as well as a considerable part of contiguous Europe, Asia, and Africa, and a range of remarkable men -- Julius Caesar (who is the pivot of the series) Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Crassus, Cicero, Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony for the modern world), and Octavius/Augustus Caesar, among many others -- and women too -- Caesar's mother Aurelia, and Cleopatra chiefly. While "The First Man in Rome" (1990) and "The Grass Crown" (1991) give an overview of Roman politics, policies, and wars from 110 BCE to 80 BCE, "Fortune's Favourites" (1993) introduces Julius Caesar, who takes centre stage in the next three - "Caesar's Women" (1996), "Caesar" (1997), and "The October Horse" (2002) - where his assassination after winning a protracted civil war ignites another. "Antony and Cleopatra" (2007) continues the story down to this duo's eventual defeat and suicide in 27 BC. The series may deal with a specific epoch but has a wider relevance - in how the Roman Republic's declined amid the conflict between elites and populists over which course of action the state should pursue - an issue of relevance today too.

Roman Republic's legacy and the modern world

- by Rinku

- April 09, 2023 2 minutes

Roman Republic's legacy and the modern world.