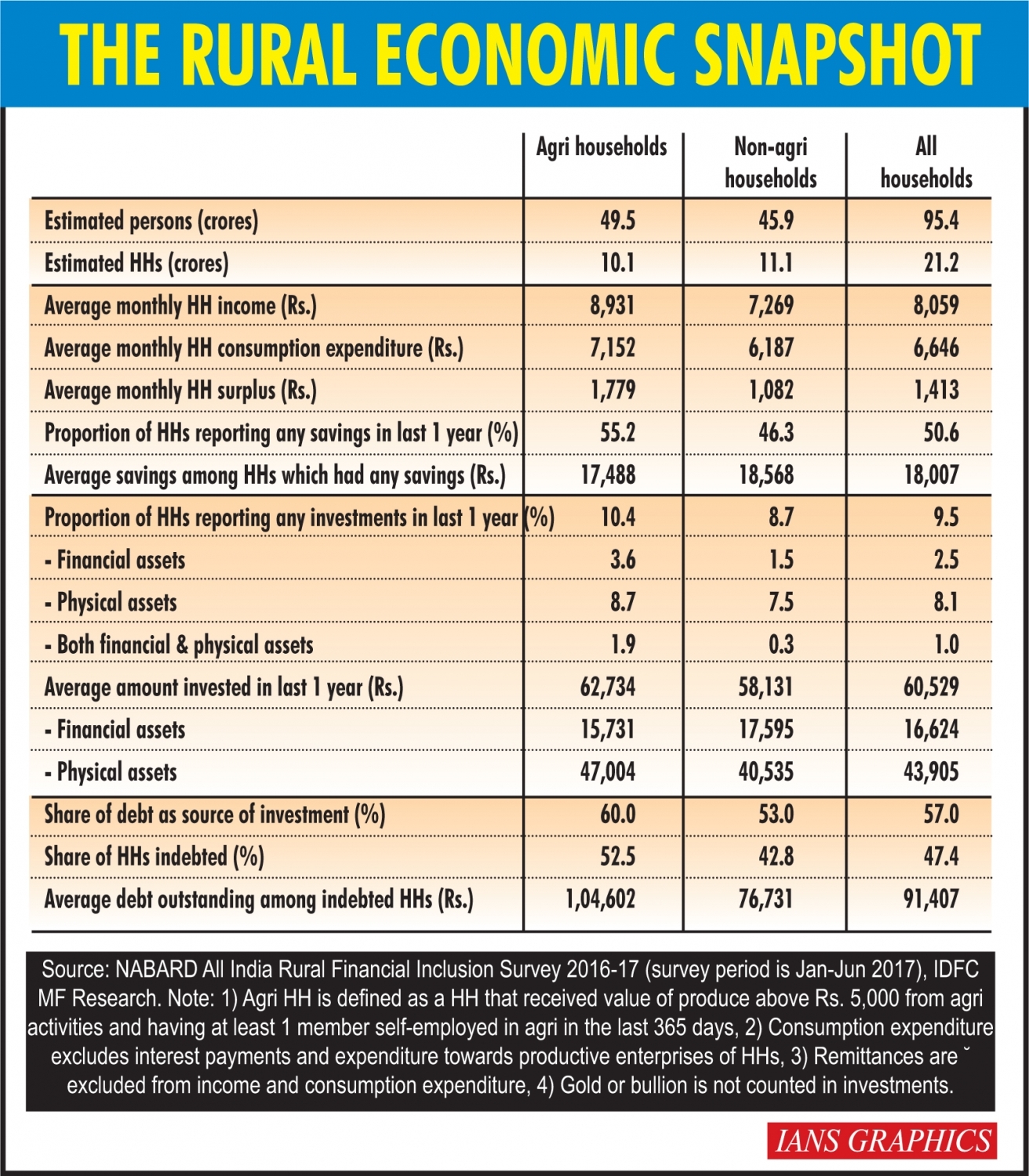

BY SREEJITH BALASUBRAMANIAN One of the major reasons EMs are forecasted to register less negative growth in 2020, vs. AEs, is the higher share of agricultural output. In India, there is optimism around agriculture, and thus rural, being the brighter spot in a contractionary growth year. The RBI Governor, in the recently released MPC meeting minutes noted rural indicators have shown a sharp revival which, if sustained, can provide support to demand going forward. In this note, we look at the current situation and the structural nuances of rural India to gauge the legitimacy of this optimism and the need for a nuanced policy approach. Rural status - Agri does well and government extends support but... Agriculture has been the brighter spot with crop-area sown in the ongoing Kharif season witnessing positive year-on-year growth in all categories, led by rice and oilseeds as south-west monsoon season rainfall this year has broadly stayed healthy (8 per cent above the long period average as on August 26 as per IMD). With Rabi sowing season (October-December) to follow, and forecasts of La Nina conditions which favour good rainfall and thus hopefully good reservoir levels and soil moisture, the two consecutive seasons could act as a natural buffer to absorb some of the excess rural labor. The key would be to ensure conversion of sowing to harvest this season, next season sails through smoothly and the sticky issue of lower price realization for farmers at least does not get amplified by the current uncertainty. Government spending on agri & rural, sale of tractors and support through MGNREGA have all been positive too, but it is probably still a case of over-optimism. Firstly, agriculture is only 18 per cent of GDP while rural as a whole is 47 per cent. Secondly, nominal wage growth was weak even pre-Covid for both agri and non-agri rural India. Real wage growth was negative since late-2019 as construction activity was also weak, which attracted surplus labor to agriculture. With labor migration from urban to rural after the onset of Covid-19, there is even higher labor supply in rural which not only reduces wages further, but simply may not find enough avenues for work as the equally important non-agri rural economy could be under greater pressure from lower demand. Some of the recent news on return of workers to urban India should be seen in this light and not yet as restoration of normalcy. The spread of the virus is also now more towards the rural economy. The good part is mortality rates have reduced and this has been broad-based across most states. Overall recovery rate has also risen. While it is well understood new cases are no longer concentrated in Maharashtra, Delhi, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat (total share of 66 per cent of outstanding cases at end-June vs. 42 per cent on August 25), two crucial aspects are: 1) Number of new confirmed cases in each state, adjusted for population - This shows a) the number is still rising in almost all states (except in Delhi where it has to fall further) & quite high in a handful and b) states with a higher share of rural population like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, etc. are also witnessing an increase in cases. Although a function of number of tests done (high in Andhra Pradesh, has picked up in Bihar but has to rise further in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal), it points to the higher rate of new cases and spread to rural areas which raises the risk there for employment, consumption and thus growth. 2) Positivity rate - If the rate is high for a level of testing, it points to the need to ramp up testing. If the rate is consistently low with high testing levels, it indicates the possibility of only a few undetected cases left (WHO recommends a rate below 5% for at least 2 weeks before reopening post-lockdown). This has reduced for more states in August than in July, which is encouraging, but the level continues to be high in many states. Thus, the way forward is to stick to higher testing on an ongoing basis to get or keep the positivity rate sustainably lower. While the more-rural states unsurprisingly have a much-higher average share of agriculture in their respective overall outputs, their lower fiscal space even pre-Covid in terms of higher fiscal deficits and outstanding liabilities is also noteworthy. For e.g., the average outstanding liabilities of Maharashtra, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu in FY19 was 19 per cent of GDP but it was 32 per cent for Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. This implies the requirement now of more financial resources by even the states with higher debt. So, while the virus is now spreading to rural and to some of the more fiscally constrained states, the likelihood of it posing a major risk to agriculture could be less. Given agri was exempt even from the earlier nationwide lockdown and the support it has been providing to employment, state governments are unlikely to impose very strict restrictions on agri during local lockdowns (unless in extreme situations) but the response of cultivators and wage labourers to perceived health risks will be equally important. However, this optimism on agri need not translate into rural outperformance. Comprehending the structure of the rural economy is critical to understand this and to evaluate/construct rural policies. Rural economic structure - much more than just agriculture and MGNREGA We list out some of the fundamental aspects of the rural economic structure below, based on our inferences from the NABARD All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey of 2017: Agri vs. non-agri -Importance of non-agri HHs in rural India - Of all the rural HHs, share of non-agri is higher at 52 per cent. It ranges from 22 per cent to 97 per cent among states and 14 of the 29 states have a share above 52 per cent. -More number of agri HHs have non-zero savings but their average savings are lower - Agri HHs earn, spend and generate more surplus. More of them have savings but they save a lesser amount than non-agri HHs. -Higher investment by agri HHs - More agri HHs invest but most of it is in physical assets required as part of agri production and not discretionary or for personal purposes. The share of debt used in such investments is also higher. Although a higher number invest in financial assets too, their average investment is lower. -Higher debt burden of agri HHs - Given the lower savings, higher investment needs and the vagaries in agri production, many more agri HHs are indebted and their average debt outstanding is also quite higher. -Small land size and asset ownership among agri HHs limit potential to raise output - Among agri HHs, although the average size of land held is 1 hectare, 67 per cent of them actually hold less than 1 hectare and only 5 per cent own tractors. -Disparity across states - Although averages are used, there is wide disparity across states for most variables due to the difference in rural economic structures. For e.g., average savings among all HHs which had any savings ranged from Rs 8,411 in Tripura to Rs 90,103 in Punjab where only 21 per cent of households reported any savings, the lowest among all states. This points to the concentration of savings in Punjab, although it is a high-saving state. Employment and wages -Farming employs only 1/3rd and MGNREGA - 4 per cent of rural population aged above 15 - 33 per cent is self-employed including farming, 27 per cent is engaged in casual wage labor in public works ex-MGNREGA, 17 per cent have regular salary/wage and only 3.7 per cent is engaged in wage labor under MGNREGA. Unfortunately, 59 per cent of women attend to domestic duties only. -Higher job diversification among agri HHs - 50 per cent of agri HHs have 2 sources of income & 39 per cent have more than 2 sources but 80 per cent of non-agri HHs have only 1 source. -Wage income is very significant in all HHs - Even among agri HHs, only 35 per cent of income is from cultivation, 34 per cent is from wages and 16 per cent from government & private services. Among non-agri HHs, 54 per cent is from wage labour and 32 per cent from government & private services. This points to the high dependence of agri and non-agri HHs on wages. -Lower wage income from MGNREGA - Average monthly income of HHs engaged in MGNREGA is only Rs 1,236 vs. Rs 3,526 for agri labor, Rs. 5,082 for non-agri skilled labor, Rs 4,921 for non-agri unskilled labor, Rs 4,988 for trading & shop keeping and Rs 10,347 for government & private jobs. Thus, a clear understanding of the rural structure makes us realise a 'one-size-fits-all' solution will not work and it allows policy to better appreciate the tradeoffs involved and focus separately on agri & non-agri, agri-land-owners & agri-wage-labourers, short-term & long-term, adequacy of measures, etc. Accordingly, existing policies could be enhanced (easier in the short-term) or new ones could be launched with a focus on execution. Government support so far for agri HHs has been mainly through the PM-KISAN scheme, exemption from lockdown and ensuring availability of inputs. Number of beneficiaries who received at least one installment so far under the PM-KISAN scheme (benefits agri land-owners) is 10.2 crore, which is 21 per cent of agri HHs and the amount involved covered 7 per cent of their average monthly consumption expenditure in 2017. Government support for non-agri HHs has been primarily through MGNREGA, which as mentioned earlier, covers only a small portion of rural HHs and offers wages which are lower than other typically available options. Both type of HHs have benefited from the Rs 500 per month cash transfer to 20.4 crore women and free rice, wheat & pulses distribution scheme unveiled in March which covers part of their food related expense. A nuanced policy mix needed While current government support measures have helped, growth ahead for rural India would broadly depend on the path of the virus (duration, breadth and intensity), revival of urban India, consumer behaviour (changes in spending and savings behaviour) and government policies. Apart from the direct government response to contain the virus and relief measures, the focus now also has to be on effective and efficient resource allocation to provide optimal support in the deserving areas. However, skewed focus on one area alone could cause economic imbalances through over-allocation of resources. Enabling state governments could also be beneficial to effectively implement policies and allocate resources, given the high disparity in the rural economic structure. Particularly in agri, structural issues have to addressed through consistent and well-deliberated policies on procurement, stock management, offloading, export & import, trader stock limits, etc. A pre-condition to providing demand support in the current context would also be easing some of the supply-side constraints. However, the constraint is the lack of fiscal space, an issue from pre-Covid days. Fiscal deficit in FY20 was envisaged in February itself to exceed the FRBM target by 50bps on the back of lower revenue. It ended the year another 80bps higher, also owing to the national lockdown starting last week of March. As agriculture has been doing well this year and has engaged additional rural labour, the first step would be to ensure the Kharif and Rabi seasons sail through smoothly. However, given the rural economy is much bigger than agriculture and rural wages have been weak for quite some time, optimism on agriculture need not translate into rural outperformance, particularly if non-agri rural and urban segments stay weak. Further, Covid-19 is now spreading to more-rural states when almost all need to stick to higher testing to get their positivity rates sustainably lower. The fundamental structure of the rural economy suggests income, consumption, savings, investments and debt levels vary not just across agri and non-agri HHs in rural India, but also considerably across states. It points to the high dependence on wage income by both agri and non-agri HHs while MGNREGA employment and wages are low. All this calls for a nuanced approach to policy making. While the existing government support programs have been useful, growth ahead would also depend on the path of the virus, revival of urban India, consumer behaviour and growth-enhancing government policies. Agri policies should focus on the resolution of some of the structural issues. Easing some of the supply-side constraints is necessary too in the current context but the constraint now is the lack of fiscal space. (Sreejith Balasubramanian is Economist -- Fund Management, IDFC AMC)

Rural India: A case for cautious optimism and nuanced policy mix

- by Rinku

- August 27, 2020 2 minutes

Rural India: A case for cautious optimism and nuanced policy mix. (IANS Infographics)