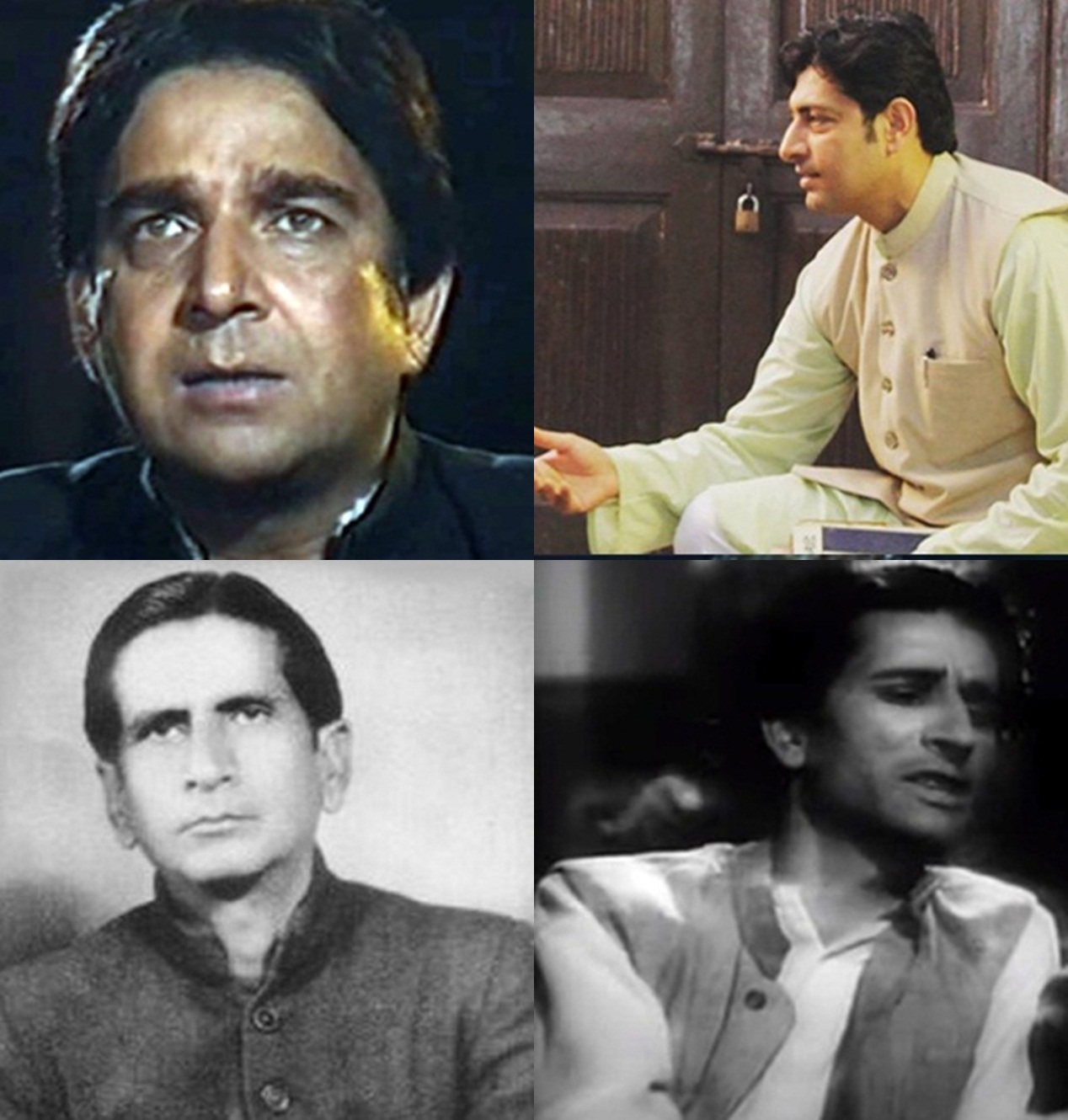

VIKAS DATTA Authors, especially poets, are feted more for their work than for their lives, with the general impression being that the latter cannot be equated with their exploits of imagination and expression. Save a handful, say Shakespeare, or Lord Byron, or in the Indian case, Mirza Ghalib, they rarely figure much in public consciousness or popular culture in their own right. This early 20th century Urdu poet was an exception. Not only did Asrar-ul-Haq 'Majaz Lakhnavi' have the distinction of being one of the first leading poets not associated with the Hindi cinema to have one of his works used in a film -- starring Shammi Kapoor no less, during his lifetime, he was deemed famous enough as to figure namelessly in a classic, with an actor resembling him reading out his poetry. Then, he was one of the six leading modern Urdu poets, chosen by veteran poet Ali Sardar Jafri, to have his life retold on the TV series "Kahkashan" (1991-92 on Doordarshan). And in 2017 -- over six decades after his untimely death -- he got his Bollywood biopic, "Majaz: Ae Gham-e-Dil Kya Karun", directed by Ravinder Singh and starring Priyanshu Chatterjee. This made him the second Urdu poet, after Ghalib, to be so commemorated. But then, Majaz (1911-55), who happened to be the maternal uncle of Javed Akhtar, fit all tropes of a poet. Besides his extraordinary skill with words, verse and metre, a literary output which encompassed revolution as well as romance, and his popularity with both the literary elite and the masses, he had a colourful and eventful life. Good-looking in his gaunt manner, he was a pin-up star of his time -- girl students of AMU and other universities were said to have hidden his photo beneath their pillows -- and his skills of repartee and quips were legendary. He also had an obsessive affair with a married woman, leading to his committal to a mental asylum when she refused to abandon her marriage. And then, his life ended in tragic circumstances -- death due to exposure on a cold December night, when his friends forgot him on the roof of a top Lucknow hotel after a session of heavy drinking. That was when he was at the pinnacle of his creativity. Majaz's ouevre straddles both romantic and progressive thought, and had a cadence and rhythm in his work that cannot fail to even impress those who may not understand Urdu. Take one of the couplets his character is shown declaiming in "Pyaasa". In this Guru Dutt film, before that haunting Sahir Ludhianvi dirge on the arbitrariness of human relationships ("Jaane woh kaise log the..."), two Urdu poets are shown, the bearded genial man in traditional garb declaiming in courtly style being Ali Sikandar 'Jigar Moradabadi'. "Majaz" recites a sher: "Roodad-e-gham-ulfat un se kya kehte kyunkar kehte/Ik harf na niklaa hothon se aur ankh mein ansu aa bhi gaye", and then, "Is mehfil-e-kaif-o-masti mein, is anjuman-e-irfani mein, sab jaam bakaf baithe hi rahe/Ham pee bhi gaye, chalka bhi gaye." These are couplets from his 1933 ghazal, which begins with "Taskeen-e-dil mahzoon na huyi voh saaye karam farmaa bhi gaye ..." and includes shers like "Ham arz-e-vafaa bhi kar na sake kuch keh na sake kuch sun na sake/Yaan ham ne zabaan hi kholi thi vaan aankh jhuki sharma bhi gaye" and "Ashuftagi-o-vahshat ki kasam, hairat ki kasam, hasrat ki kasam/Ab aap kahen kuch ya na kahen ham raaz-e-tabassum pa bhi gaye." On the other hand, Majaz is strident in his call for the artistic fraternity to not shrink from action when the coming revolution demands it. In his nazm titled "Inquilab", also of 1933, he declaims: "Phaink de ae dost ab bhi phaink de apna rabab/ Uthne hi wala hai koi dam mein shor-e-inquilab." The work employs some stark imagery of what the tumult will entail. "Koh-o-sehra mein zameen se khoon ublega abhi/Rang ke badle gulon se khoon tapkega abhi." Majaz could use his art in other situations too. The nazm "Raat-o-Rail" is an account of a train journey at night, and while reading it, you feel you are on one yourself. "Phir chali hai rail isteshan se lahraati huyi/Nim-shab ki khamoshi mein zer-e-lab gaati huyi/Dagmagaati, jhumatii, seeti bajaati, khelati/Vaadi-o-kohsar ki thandi hawaa khaati huyi" ... and so on for another 37 couplets. His most well-known work happens to be the nazm "Awaara", brought in mass public consciousness when two-three stanzas, slightly modified, were used in film "Thokar" (1953), picturised on Shammi Kapoor and rendered by the velvet-voiced Talat Mehmood. Inspired by a night-time walk on Marine Drive in Bombay, the rhythmic "Awaara" captured the essence of alienation in a teeming metropolis. "Shahr ki raat aur main nashad-o-nakaara hoon/Jagmagati jagti sadkon pe awaara phirun/ Ghair ki basti hai kab tak dar-badar mara phirun/Ae gham-e-dil kya karun, ae vahshat-e-dil kya karun" And now sample its inspired imagery: "Ye rupahli chhaaon ye akash par taaron ka jaal/ Jaise Sufi ka tasavvur, jaise aashiq ka khayaal/Aah lekin kaun samjhe, kaun jaane dil kaa haal / Ae gham-e-dil kya..." But the best is: "Raaste mein ruk ke dam le lun meri aadat nahi/Laut kar wapas chala jaun meri fitrat nahi/Aur koi hamnawa mil jaaye ye qismat nahi / Ae gham-e-dil kya..." And then, there are countless other examples of his inspired poetry, especially on romance: "Inka karam hai inki mohabbat 'Majaz'/Kya mere naghme, kya meri hasti", or "Hoti hai is mein husn ki tauheen ae 'Majaz'/Itna na ahle-e-ishq ko rusva kare koi", but also "Kahan ka rehnuma aur kaisi raahen/Jidhar badhta hoon manzil dekhta hoon". And then, the anecdotes of Majaz are legendary, showcasing his quick wit. But the best is when disturbed at a mushaira by cries of an apparently hungry baby in the audience, Majaz softly said: "Naqsh fariyaadi hai kis ki shokhi-e-tahreer ka... ("of whom is this applicant a copy" or in other words, who are the parents?). This happens to be the first line of Ghalib's first ghazal and only a thoroughly ingrained poet could have used it instantly to fit the occasion. That was Majaz for you. (Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

Majaz Lakhnavi: His colourful life and ageless poetry

- by Rinku

- January 09, 2023 2 minutes

Majaz Lakhnavi: His colourful life and ageless poetry.