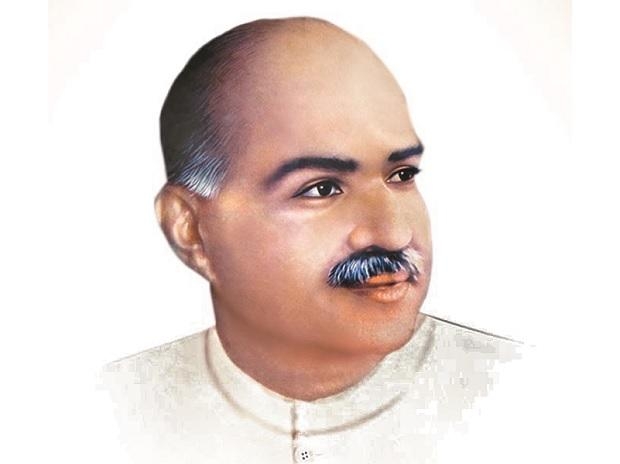

By Shantanu Guha Ray New Delhi, July 4 (IANS) A monk turned lawyer's public interest litigation (PIL) in Calcutta High Court to seek reasons behind the mysterious death of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee has stirred a hornet's nest in the Bharatiya Janata Party. The BJP, which calls the former barrister and academician its father figure, has done little to probe his death except talking about India's first industries minister at big events, lighting lamps and creating study centres which largely remain within files. Kolkata-based Samarjit Roy Chowdhury has asked for an inquiry commission headed by a retired chief justice of India. The application will come up for hearing by the end of July, 2021. Roy Chowdhury, who shared details of his petition with his reporter, said Mookerjee, who died on June 23, 1953, was detained without trial by Sheikh Abdullah's government after his arrest in Kathua on May 11, 1953. Government records claim Mookerjee died in the custody of Jammu and Kashmir Police. He was provisionally diagnosed with a heart attack and shifted to a hospital but died a day later. Virtually nothing is known about the cause of the death of Mookerjee, a minister in undivided Bengal and in Nehru's cabinet. Mookerjee, the youngest vice chancellor of the Calcutta University at 33 was a prominent Opposition leader and founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. The Jana Sangh eventually gave birth to the current day BJP. "I am surprised at the silence, we must know how Mookerjee died," said Roy Chowdhury. Political cognoscenti in India feel the PIL, if accepted, could open a pandora's box in politically-sensitive India where similar efforts have opened up many unheard details of national leaders like Subhas Chandra Bose and Lal Bahadur Shastri. In both cases, movies have been made and tomes written to highlight what many claim was gross disparities in what historians peddled for many years. The PIL takes note of the correspondence between PM Jawaharlal Nehru and Mookerjee's mother, Jogomaya Devi. On June 30, 1953, Nehru wrote to Jogmaya Devi, Mookerjee's mother, conveying his condolences. On July 4, Devi responded: "My son died in detention, detention without trial. You say, you had visited Kashmir during my son's detention. You speak of the affection you had for him. But what prevented you, I wonder, from meeting him there personally and satisfying yourself about his health and arrangements?... Ever since his detention there, the first information that I, his mother, received from the Government of Jammu and Kashmir was that my son was no more. And in what cruel cryptic way the message was conveyed." Roy Chowdhury claimed in his petition that medicines administered to Mookerjee must be probed because Mookerjee had refused to be injected with the medicine. As per government records, Mookerjee was arrested upon entering Kashmir on May 11, 1953. He and two of his arrested companions were first taken to Central Jail of Srinagar. They were later transferred to a cottage outside the city. Mookerjee's condition started deteriorating and he was diagnosed with dry pleurisy from which he had also suffered in 1937 and 1944. The doctor prescribed him a streptomycin injection and powders, however, Mookerjee informed him that his family physician had told him that streptomycin did not suit his system. The doctor, however, told him that new information about the drug had come to light and assured him that he would be fine. On June 22, he felt pain in the heart region, started perspiring and started feeling like he was fainting. He was later shifted to a hospital and provisionally diagnosed with a heart attack. He died a day later. What is interesting is that in 2004, Atal Bihari Vajpayee claimed in Parliament that Mookerjee was murdered in a "Nehru conspiracy". Roy Chowdhury said he found it extremely surprising that the BJP, whenever it was in power, refused to push for a probe into Mookerjee's mysterious death. "Would you not probe the death of the father of your party? Strangely, the BJP did nothing to uncover the mystery," said Roy Chowdhury. Roy Chowdhury said on November 27, 1953, a resolution was moved in the West Bengal Legislative Assembly to hold an inquiry into the circumstances of Mookerjee's death while in detention in Kashmir. It argued for holding an inquiry through a commission headed by a Supreme Court judge. Surprisingly, an Assembly member from the Congress party, Shankar Prasad Mitra, moved an amendment to this resolution asking for the words "for holding an inquiry", to be substituted with "for requesting the Government of Jammu and Kashmir to hold an inquiry". Worse, Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, then CM of West Bengal, declined the move for an inquiry. The PIL says what had been asked for was an inquiry by a SC judge who could take cognisance of evidence from across India, including Kashmir. "In this case, the Kashmir government was the accused party. How could it then sit in judgement over this inquiry? But members of the Congress, including Roy, argued in favour of the amendment. The Congress, in effect, sought acceptance of the amendment, and succeeded. The West Bengal government forwarded the resolution passed in the Assembly to the Ministry of States (Kashmir section), Government of India. This letter was received on February 23, 1954. After six months, the matter was eventually processed in the Ministry of States," said the PIL. The PIL includes the following observation from the relevant file in the Ministry: "It is for consideration whether we may inform the Government of West Bengal that as the matter primarily concerns the Government of J&K, the Government of India did not consider it proper to pursue the matter. When the request for an inquiry into the circumstances of Mookerjee's death was raised in Parliament, the attitude which we adopted was that this was a matter which concerned the Government of J&K alone. The resolution passed by the West Bengal Legislative Assembly is consistent with this stand since it only asks the Government of India to pass on the request to the Jammu & Kashmir Government. We have now two courses open to us: We may either send the copy of the resolution and proceedings to the J & K Government for such action as they may consider necessary; or we may return the proceedings to the West Bengal Government and ask them to address the J&K Government themselves. While the latter course might be strictly correct one, it would have the effect of rebuffing the Government of West Bengal where Mookerjee's death has agitated the public mind very much. There may therefore be no harm if we adopt the first alternative. I do not think this is likely to give rise to any misunderstanding with the J&K Government." The PIL says K.N.V. Nambisan from the Ministry of States signed this note on September 7, 1954. The first course was agreed upon by both the secretary and the minister. On September 22, 1954, the Ministry of States forward the resolution to the Chief Secretary of Jammu and Kashmir, for such action as considered necessary. Nothing came out of this routine letter sent by the Ministry of States to the Government of J&K. The PIL further said a notice for a starred question was given in Parliament on August 19, 1954 -- the Minister of Home Affairs was asked to clarify whether the Bengal CM had visited Kashmir in June 1954 and made an inquiry about Mookerjee's death. On July 20, 1954, the Ministry of States had asked the Jammu and Kashmir chief secretary about the reported visit of Roy. On July 19, 1954, the Ministry of States had written to the Lok Sabha secretariat stating that they had no information except what appeared in the newspaper about the stay of Roy in Jammu and Kashmir. The letter further stated that the circumstances relating to the death of Mookerjee, while in detention, was a matter which concerned the Jammu and Kashmir government, not the GoI. On August 5, 1954, Ghulam Ahmad, chief secretary of Jammu and Kashmir wrote to V. Narayanan, joint secretary to the GoI (Ministry of States): "Dr B.C. Roy did come to Kashmir for a holiday and spent about a month here. During his stay he visited various beauty spots in the Valley. He did see the bungalow where Mookerjee was putting up during his stay in Kashmir as well as the room in the hospital to which he had been removed prior to his death. Col. Sir Ram Nath Chopra, our Director Health Services, took him to the hospital one day and Dr B.C. Roy might have made some verbal enquiries on the spot. You will, therefore, see that no official inquiry was held by the Doctor and as such no report could have been submitted by him. The question in the Lok Sabha may, therefore, be replied suitably on the basis of this information." Interestingly, PM Narendra Modi remembered Mookerjee in his 45th Mann Ki Baat show. "His efforts towards national integration will never be forgotten," said Modi. The PM had said that while Mookerjee was associated with many fields, education was close to his heart. "Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee was associated with many fields, but the areas which were closest to his heart were education, administration and parliamentary affairs; very few people would know that he was the youngest vice-chancellor of the University of Calcutta at merely 33 years of age," said the PM. Modi also said it was on Mookerjee's invitation that Rabindranath Tagore addressed the convocation in Kolkata University in Bangla. "Very few people would also be knowing that in 1937, on the invitation of Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore addressed the convocation in Kolkata University in Bangla. This was the first time under the British rule that the convocation in Kolkata University had been addressed in Bangla. All eyes are now on the Calcutta High Court. If it's admitted, then work will start on one of India's biggest political mysteries. If not, the father figure of BJP will be remembered during lighting of lamps during mega functions, or confined to files. Mookerjee's home, for the records, is currently in a total dilapidated state in South Kolkata, haunted by bats and insects. (Shantanu Guha Ray, India Editor, Central European News (CEN), Vienna can be reached at shantanu@cen.at)

A PIL for Syama Prasad Mookerjee

- by Rinku

- July 04, 2021 2 minutes

BJP to observe Syama Prasad Mookerjee death anniversary in Srinagar